History is often considered a stale, boring subject filled with places, dates, and people. This is not true because despite the passage of time and regardless of who they were, where they came from, or what they did – at some level, we can identify with these people from the past, and make a connection. This comes about through research. My personal experience came about through serendipity when an archivist at the Minnesota Historical Society “introduced” me to a fascinating St. Paulite, Ruth Cutler, as I did research on Minnesotans in World War One.

While I wanted to focus on her mission of overseas work, I discovered the loss she experienced was inexorably tied to her personal spiritual beliefs and life story.

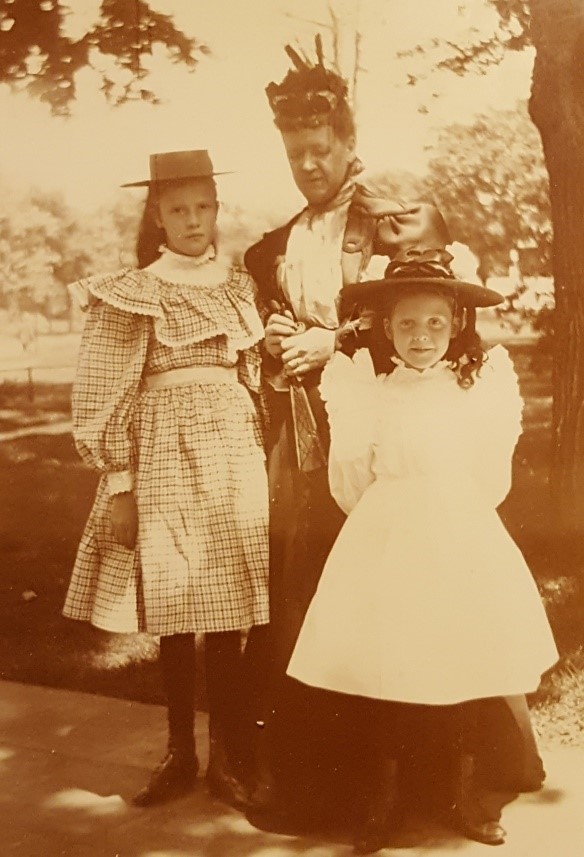

Born in 1890, Ruth Cutler was the youngest child of prominent St. Paul family, Edward and Lucy Cutler. Growing up, Ruth compiled a steady stream of diaries and journals describing her life’s curiosities and events. She was the first woman in her family to achieve a college education and the first to enter the workforce as a social worker. Emblematic of the Progressive Era, Ruth, like many of other women, possessed a strong desire to make the world a better place through service overseas. When America entered the war in 1917, the Red Cross served as the major conduit for women seeking this kind of work. However, her efforts to join the humanitarian relief effort overseas during the Great War were stymied, in part, due to her mother’s earlier diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer in May of 1915.

Assuming the role of caretaker, Ruth chronicled her mother’s slow demise, describing the early use of radium therapy to mitigate the disease. But she refrained from using the word ‘cancer’ let alone ‘breast cancer’ in her diaries or journals. Only the county death records and Oakland Cemetery burial files provide the definitive diagnosis.

Although radium therapy (a new technology) helped, by October of 1916 the family’s doctor delivered the grim prognosis and put a damper on Ruth’s overseas plans. Over the next three years, the family endured the slow and agonizing deterioration of Lucy Cutler. At the close of April 1918, all was revealed when Ruth poured out her grief in her journal. Near the end, her mother made it a point to tell her how much she loved her youngest daughter, then Ruth wrote. “She went, at last, unconsciously at 1:30 on Tuesday morning April 9 (1918) – just 8 years from the very day Grandma Dunbar died. I was sitting up with her I noticed the change coming and called for the others. Her dream had come true at last – she woke up well.” Ruth concluded “We know she is near us for we feel a peace and comfort which otherwise we could not.” Afterward, she wrote of the immense relief the entire family felt, exclaiming “…we can yearn for her, but we can never grieve for her.”

In the wake of her mother’s death, Ruth sought renewal and purpose. Her late mother had always remained steadfast in support of Ruth’s desires and she considered the best way to honor her mother was serving in something greater than herself – making something good out a tragic loss.

On May 6, 1918 Ruth chimed “Today I have taken a turn in the road which is bound to be a great moment to me all the rest of my life. I have registered for nurse’s training at the University [of Minnesota] Hospital. Perhaps it is the start to a greater moment. There are many a one we take each and every day, little realizing what hangs on the choice we unconsciously take this preference to that.” Weighing her options, Ruth thought nursing was more vital to the war effort than social work but, in another turn, young Ruth was chosen as one of the last Red Cross workers for overseas duty. Arriving in Paris on Friday December 13, 1918 Ruth came in time to witness President Woodrow Wilson’s motorcade on its way to discuss peace negotiations. The event was the highlight of her journey.

Tragically, Ruth’s triumph was short lived. On December 16 she fell victim to influenza and died of lobar pneumonia on December 23, 1918. Within a span of nine months, the Cutler family had lost both their matriarch and their rising star.

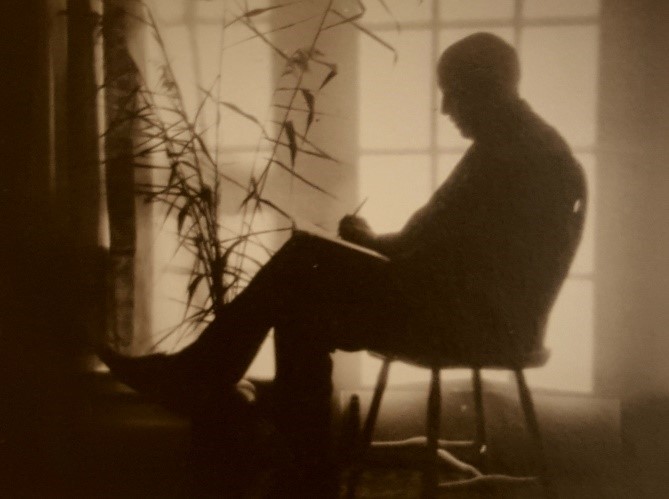

Whereas her mother’s death was expected and something they could prepare for, Ruth’s came as a complete shock to her social network and family. News of her death hit her father particularly hard. Despite his contributions to the Red Cross, and later, in 1922, financing the addition to the Swedenborg [now Virginia Street] Church in St. Paul, and dedicating it to the memory of Ruth and Lucy Cutler, Edward never overcame the loss. In the decades that followed, family photos reveal a somber looking individual.

A descendant whom I interviewed, aptly described Ruth Cutler as “venerated”. Indeed, she was. Among the many items of Ruth’s now archived by the Minnesota Historical Society, is a tiny pocketbook Ruth labeled “Recipes and Miscellaneous Writings”. Within its weathered pages is a line copied from a book published in 1915 and entitled Eve Dorme: The Story of her Precarious Life. The sentiment perfectly summarizes Ruth’s enduring spirit. Across the ages, she gently reminds us –

Best there is never any real parting between those who love – no forgetting of people who are always in our hearts. When we think of them, we live ever the happy days which we spent together until kind fate brings back again more of such days to live and remember.