This is part one in a two-part blog series. Following the free “Care for Caregivers” event we recently hosted alongside Pioneer PBS, we want to share some of the key parts of the rich discussion that followed the screening of the film “Caregiver: A Love Story,” which you can watch here. This week’s post highlights the problem of caregiver burnout and some things we should know about the related challenges and opportunities. Next week’s post will focus on helpful tips for caregivers and what all of us can do to support the caregivers in our lives.

This is part one in a two-part blog series. Following the free “Care for Caregivers” event we recently hosted alongside Pioneer PBS, we want to share some of the key parts of the rich discussion that followed the screening of the film “Caregiver: A Love Story,” which you can watch here. This week’s post highlights the problem of caregiver burnout and some things we should know about the related challenges and opportunities. Next week’s post will focus on helpful tips for caregivers and what all of us can do to support the caregivers in our lives.

“The system doesn’t recognize how it burns out the caregiver.”

That’s a quote from Rick, who struggled to care for his wife, Bambi, at their home over the final nine weeks of her life. Rick and Bambi’s story was made into a documentary called “Caregiver: A Love Story” that illuminated a significant problem plaguing many caregivers across the U.S.: The role is too difficult to manage without a vast support network, but there aren’t adequate resources to assist most family caregivers so that they are equipped to provide compassionate care while also meeting their own needs. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated this issue and brought to light the mental toll placed on caregivers.

The film was directed by Dr. Jessica Zitter, a palliative care and ICU doctor who supports patients with serious illness, many of whom are facing end of life. We recently partnered with Pioneer PBS to host a free virtual screening of Zitter’s movie, followed by a discussion between Zitter and our founder, Cathy Wurzer—who took questions from both live and online audiences. Here are four of our key takeaways from what Dr. Zitter shared about caregiver burnout:

1. The numbers help tell the story: So, why are caregivers exhausted and in need of additional support? Consider these figures:

- 10,000 Baby Boomers are turning 65 every day. We are prolonging life, which means that more people are living with serious and life-limiting illnesses for longer periods of time.

- 80 percent of people want to die at home.

- On average, people serve in the caregiver role for 4.5 years.

- 60 percent of family caregivers work, the majority full-time.

- Family caregivers who live with the care recipient, on average, spend $6,000 of their own money each year on caregiver-related duties; those who don’t live with the person they care for spend $13,000. One-third of family caregivers are earning less than $50,000 annually.

2. We need to do a better job preparing caregivers to take on that role: Most caregivers don’t realize what they sign up for when they take a loved one home from hospital, Zitter said. One of the best things health care providers can do is help them understand what their role will entail, how challenging it will be, and how important it is to set up a support system so they’re not walking the road alone. That includes learning what hospice is and is not able to offer (for example, hospice workers typically manage symptoms and medical equipment, but they can’t assist with grocery shopping, cleaning, laundry, or child care). “That awareness will provide space for the caregiver to sit within what their real situation is, accept it, honor it for themselves so they can then start to do the work of getting help,” said Zitter. “We should expect and anticipate that caregiving is going to require external support resources.”

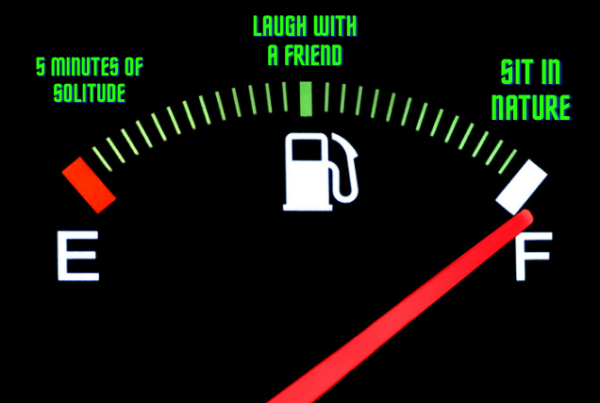

3. We may be at a tipping point for getting more caregiver support: The growing number of people needing care, the shrinking number of people able to provide it, the COVID-19 pandemic, frequent news articles about the burden of family caregiving, and a discussion taking place in Washington, D.C. right now have all heightened awareness about caregiver challenges. “I think we’re at a moment right now…which could potentially be a tipping point for this issue,” said Zitter.

4. Caregiver support is a type of advance care planning: When you’re working on your advance directive, take some time to think about and plan for who will care for you if you can’t care for yourself—and for whom you might serve as a caregiver if and when the time comes. What Zitter says she will remember when she’s a caregiver someday: “I’m going to keep in mind that there’s no way I can do that work if I don’t have resources built in to support me…I’m going to have to plan it out because it’s a marathon and I don’t want to run out of steam.”